Hello, internet! Tom here.

It is, once again, my turn to entertain you for a week here on The Art of Writing. It’s been a while since my last post, and I have to confess that my writing hasn’t been going very well in the interim. I feel a little disingenuous dishing out writing advice when I’m not doing much writing myself, but writing a blog post can be a good of way of solving your own problems as well as helping other people with theirs. So today’s post is going to look at why we sometimes find it hard to write, and how we can get past that.

The German novelist Thomas Mann once wrote that “A writer is somebody for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” I entirely agree with him. I have always wanted to be a writer, I have had a talent for writing since I was ten or eleven years old, and I have honed that talent over time to the point where I consider some examples of my writing to be quite good. I still can’t think of anything else that fills me with the same passion as writing, or anything that I want to do more than creating entire worlds and using those worlds as the backdrops for entertaining stories. But none of that means that I am ‘a good writer’, because our definition of a writer must be ‘a person who writes’, and our definition of a good writer must be ‘a person who writes a lot’. I do not write a lot. For someone who would like to write for a living, I am extremely good at avoiding writing, and there’s an obvious problem there. If we went to a party and met someone who said that they wanted to be a rock star, but then we found out that they hadn’t played their guitar for weeks or written any music in the last few months, then we’d smile and nod and walk away and find someone else with whom to quietly share our scepticism about the aspiring rock star’s artistic ambitions. That person at the party is us, if we spend months without writing anything and still go around considering ourselves to be writers.

I have a fairly uncompromising view of what constitutes a writer. I think a writer is a person who writes about 3,000 words a week (or preferably more), even if their cat just died or their significant other is hurling breakable objects at them or they’re suffering from an advanced case of gout. I do not meet this definition. I went through a period last year of reliably writing 3,000 words a week, but now I barely manage 500, and I don’t have a cat, or an angry spouse, or even a mild case of gout (that I know of). I fall well short of my own estimations of how much a writer should write, and I feel horribly guilty about it. But that is how much I think a writer should ideally write: or perhaps that’s how much I’d have to write every week to really feel like I deserved to go around calling myself a writer.

You may disagree with me. You may think that “writers” are writers because of destiny and cosmic predisposition, and that you can be a “writer” on some indelible vocational level even if you don’t write anything on a regular basis. If you think that, then keep reading.

There are legitimate mitigating circumstances in which aspiring writers might be forgiven for not meeting my definition (although that doesn’t stop them from not meeting it). Selayna, my fellow blogger, has a crazy schedule and works much harder than I do. If she wanted to write 3,000 words a week then she’d have to do it all during the weekend. Some authors do that, but I’d rather Selayna was using the weekend to get some rest and talk to her loved ones and do whatever it is that normal people do during the weekend when they don’t have writing ambitions.

Unlike Selayna, I have plenty of free time. My own circumstances leave me with no excuse not to write, and I am left wondering why – if I truly want to be a writer – I find it so difficult to get into a productive, reliable writing routine?

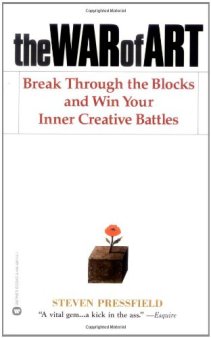

In an attempt to answer this question, I read The War of Art by Steven Pressfield.

Pressfield wrote The Legend of Bagger Vance and moved on to write epic works of military historical fiction, several of which are on the reading list at US military colleges. He also writes self-help books, and The Art of War: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles, is a self-help book targeted specifically at struggling writers.

I have a deep-grained and inherent scepticism of self-help books, especially when other people recommend them to me, but in Pressfield’s case I can definitely advocate that you should get yourself a copy. The first read-through left me feeling energized and optimistic, and if you’re feeling discouraged or poorly motivated as a writer then you can open it to any page for an instant self-esteem boost or kick in the ass. He also writes a lot about the concept of ‘Resistance’ – that force that sometimes makes it so hard for us to get around to doing the things we want to do. He writes, “the more important a call or action is to the soul’s evolution, the more Resistance we will feel toward pursuing it”.

The War of Art made me think a lot about how I’m viewing my writing, and how I’m viewing myself as a writer. Pressfield places a lot of stress on the differences between an amateur writer and a professional. An amateur has different habits, different ideas of what success will look like, and different levels of emotional investment. The key lesson I’ve taken away from his book is that it’s a mistake to get too personally invested in what I’m writing. That may sound surprising, but it makes a lot of sense once you think about it.

Pressfield doesn’t necessarily think that we should aspire to define ourselves as writers. He thinks that we should simply be people who write stuff, and publish it, and don’t allow our writing to get tangled up in our own personal aspirations. He writes that, as professional writers:

“we do not overidentify with our jobs. We may take pride in our work, we may stay late and come in on weekends, but we recognise that we are not our job descriptions. The amateur,on the other hand, overidentifies with his avocation, his artistic aspiration. He defines himself by it. He is a musician, a painter, a playwright…the amateur composer will never write his symphony because he is overly invested in its success and overterrified of its failure. The amateur takes it so seriously it paralyzes him.”

That paragraph really made me think about how I’ve been approaching my writing. I have absolutely been paralysed by my writing, because I have absolutely been ‘overidentifying with my avocation’. That surprised me when I realised it. I had considered myself an uncompromising pragmatist, who didn’t subscribe to any ideas that writing was ‘in my blood’ or that I was a ‘writer by nature’. Yet here I was allowing my own aspirations and dreams and fears to prevent me from putting words on the page. Succeeding as a writer has seemed so important to me for so long that it has stopped me from actually writing, because I was scared that I wouldn’t be good enough to succeed: a Catch 22 scenario that would, inevitably, lead to me not succeeding or writing anything.

For myself and other writers like me, I think the key to avoiding that paralysis is just to sidestep it, face the facts, and redefine success. In my pursuit of success as a writer, I’ve acquired enough experience and skills to become decent at writing, but I have also allowed the pursuit of success – and fear of failure – to hold me back. I think the trick is to forget about success or failure, exit that mindset, and find a good use for the skills I’ve gained: almost as if I’m giving up on ‘being a writer’ and just writing something instead. I can try to write the next great fantasy series, allowing my personal aspirations and delusions of grandeur and sense of self-worth to get wrapped up in what I’m writing, and allowing them to paralyse me. Or I can roll up my sleeves and put my talent to good use, writing readable B-list fantasy books that will bring home the bacon. That seems a lot more achievable, and a lot less stressful.

Thank you for sharing this. I think the same struggle can be present with any creative ability, but maybe writers fall into this trap more easily because thinking about words is almost like writing with them. 😉

I would call myself a writer, and no, I don’t write a lot. But this is not merely over-identifying with a vocation or “calling.” It’s just something I can do. Have you ever met someone who can do math in their head, especially one who can do it quickly? It’s like their brains are wired for handling numbers. Mine isn’t wired for numbers, but words. Doesn’t matter if I’m writing an email, technical instructions, or a personal letter. I am in my element when I’m crafting with words.

As a web site manager, my job description doesn’t say much about writing. I’ve written a couple of articles when we really needed the content, and I think my boss wishes I had time to write more. But if my immediate coworkers need something edited, or are trying to find the right word, they send it to my red pen.

Maybe this doesn’t make a writer; maybe I’m only good with words. But either way, writing is just my thing, ya know?